Welcome to Part Two of our Series Exploring the Effect Wildfires Have in the United States & Globally. If you Missed Part One, Start Here!

What toll are unprecedented wildfires taking on our environment, society, and local economies in 2021 as we look toward the future? Environmental or socio-economic impacts from wildfires in the United States and worldwide have already been steadily increasing over the past several decades.

Fires of the magnitudes we are now seeing as a “new normal,” such as the “Dixie” fire, which at the time of publishing this article has burned for over a month and claimed at least 807,396 acres of land, adversely impact natural ecosystems, air, and water quality/supply. These conflagrations also affect local economies –– from tourism to property values and available employment.

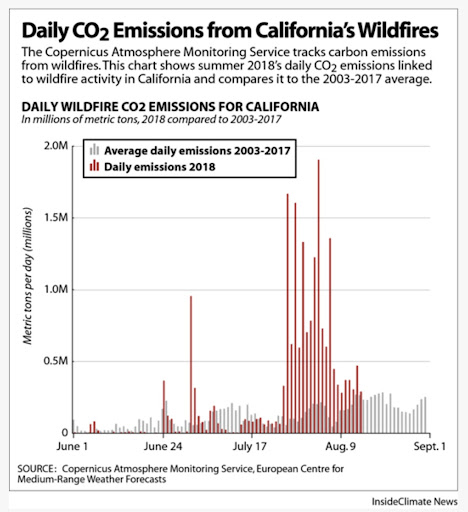

It is challenging to calculate the exact cost we are paying as citizens financially in taxes or environmentally in CO2 emissions from these wildfires. However, scientists estimate that wildfires emitted around 8 billion tons of CO2 per year for at least the past two decades. In 2017, even before the catastrophic fires of 2018, total global CO2 emissions reached 32.5 billion tons, according to the International Energy Agency.

What about the costs? According to data from the National Interagency Fire Center, federal wildfire suppression costs in the United States have spiked from an annual average of approximately $425 million from 1985 to 1999 to $1.6 billion from 2000 to 2019. These numbers do not include the cost of rebuilding lost communities.

➡️ If the consequences from this noticeable increase in wildfires are occurring year after year, why isn’t there more readily available information about wildfires' far-reaching effects?

The air quality measurement tools produced at Met One Instruments Inc. are used every day on the front lines to assist firefighters and scientists worldwide with testing our air quality during wildfires. We feel compelled to share our findings, considering the global wildfire crisis unfolding in 2021, with mass wildfires plaguing the planet. Using our resources and experience in this field since 1989, we are honored to have the ability to assist with educating the public today about the environmental & socio-economic toll these events are taking on our communities. Let’s get started.

What are the Environmental Impacts of Wildfires?

We should preface that Wildfires are a normal part of the cycle and renewal process of forests. However, not on the scale that has been escalating over the past 20 years. Case in point, the majority of “wildfires” are started because of the negligence of humans (84% has been estimated). Have you ever stopped to ask yourself what happens to the environment during and after a wildfire is extinguished?

It’s not a stretch of the imagination to grasp the devastation that transpires in a geographic area after a large wildfire. Everything is scorched. Homes and buildings in its path burn to the ground. Vehicles melt. Trees that took decades to hundreds of years to establish are lost. Many animals perish. Animals that survive are forced to flee the area to find a habitable forest and food. The soil is compromised and, while resilient, can be devastated for decades after a particularly massive fire destroys the land.

➡️ The primary concern after a Wildfire is air pollution. Air quality is one of the most significant perils associated with wildfires—for a valid reason.

“In 2015, smoke from wildfires in Palangkaraya, Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), pushed the air quality index to 2,000. The air during that fire season caused 500,000 people to develop significant respiratory infections and was estimated to have caused the premature deaths of 100,000 people.” — What is Left in the Air After a Wildfire Depends on Exactly What Burned

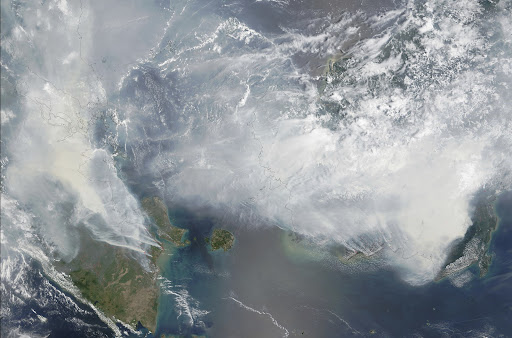

The haze pictured above lasted for months and affected Indonesia and Thailand, Vietnam, Brunei, Cambodia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore. When large-scale wildfires occur, massive amounts of smoke are released into the atmosphere.

This smoke is made up of a complex mixture of gases, microscopic particles, and water vapor. Particulates that make up the smoke are less than 2.5 microns in diameter (approximately 1/70th the size of a human hair). Homes or buildings claimed by a wildfire release hazardous byproducts into the air due to chemicals and building materials that go up in smoke, never meant to be burned in the first place.

The technical term of the most hazardous monitored airborne matter is PM2.5, which references particulate smaller than 2.5 microns (micrometers). These particles are so tiny our bodies have a difficult time filtering them out of our airways. Particulates of this microscopic size can lodge deep in your lungs and pass into your bloodstream, which in turn compromises your breathing and can add stress to the heart. Particulates also irritate our eyes and cause congestion. People with chronic respiratory or cardiovascular issues have an elevated risk of experiencing severe health concerns during a wildfire.

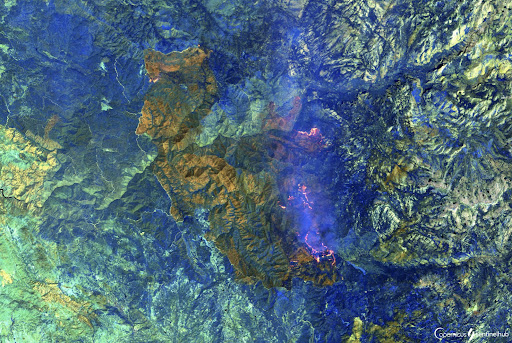

California Wildfires (2018) Smoke Penetrating the Atmosphere –– by SentinelHub Wikimedia Commons

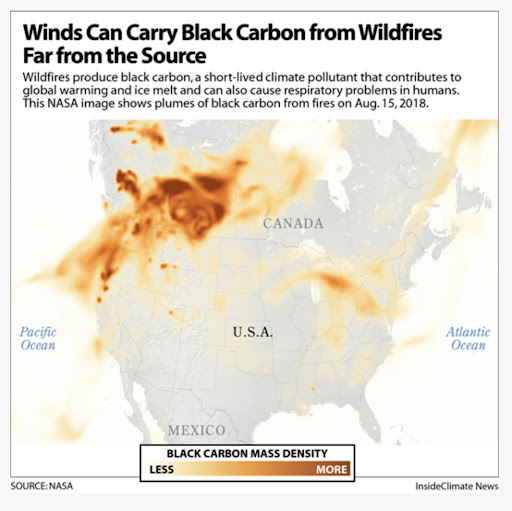

Smoke plumes from massive fires such as the Dixie fire currently burning in California can push the air pollution produced high into the atmosphere. These large plumes of smoke will travel along with existing winds. The incomplete burning of forests produces large amounts of carbon monoxide. Its levels are highest during the smoldering stages of a fire and can cause various risks to human health.

Wildfires can also affect the water quality of streams, rivers, lakes, and reservoirs for years and even decades following a catastrophic fire. Another significant impact of wildfires is the considerable increase in stormwater runoff. After the loss of vegetation, the soil becomes “hydrophobic,” meaning it cannot absorb rainfall.

Vegetation slows precipitation down and helps the water gradually seep into the ground. After a wildfire, the compromised soil cannot absorb moisture as it would under normal circumstances. The result is an increase in runoff, which provides a pathway for debris or sediment to rivers, lakes, and reservoirs and an increased risk for landslides.

➡️ Another environmental concern — the smoke & ash from wildfires contaminate drinking water.

Did you know that approximately half of the water supply in the southwestern United States comes from natural sources in our forests? Areas that wildfires have cleared are prone to greater erosion rates, increasing the downstream aggregation of pollution and sediment in rivers, lakes, or reservoirs. The potential for consequences from past, current, and future wildfires on water quality in the area is a fundamental problem for months or years after the fire has been contained.

What are the Socio-Economic Impacts of Wildfires?

“The social cost of carbon (SCC) is arguably the single most important concept in the economics of climate change.” –– The Mortality Cost of Carbon

A study released in Nature Sustainability, December 2020, by the University of Irvine, China's Tsinghua University, and other institutions found that California’s 2018 wildfires caused $150 Billion in damages. The group used physical, epidemiological, and economic models to gain a comprehensive understanding of the impact of that season of wildfires. In 2018, 1.9 million acres burned, making it the deadliest and most disastrous wildfire season in Californian history.

“Tallying the damage, the team found that direct capital impact (burned buildings and homes) accounted for $27.7 billion, 19 percent of the total; $32.2 billion, 22 percent of the whole, came from health effects of air pollution; and $88.6 billion in losses, 59 percent, was indirectly caused by the disruption of economic supply chains, including impediments to transportation and labor.” –– sciencedaily.com

There is very little information available about the socio-economic impact that natural disasters have on our communities as a whole. Several contemporary studies we reviewed, such as “The Effects of Large Wildfires on Employment, Wage Growth & Volatility in the United States,” published in the Journal of Forestry, reported that during the wildfire, these communities temporarily increased their employment numbers because of federal funds pouring in and the human resources required to suppress the wildfire.

It is noted in this study that wildfires strain community development efforts and create inequities or conflict over fire management and recovery decisions. Also, the following years are noticeably more volatile regarding employment opportunities in areas affected by destructive wildfires. Wildfires' effect on the socio-economic attributes of a specific community depends heavily on whether or not they can absorb resources needed to participate in the suppression effort, postfire recovery, and restoration efforts.

Yet, many of the studies produced by Universities that we reviewed about wage growth and volatility as it relates to wildfires do not bother to note or mention: At what cost in the long-term? The scope of these studies are unfortunately short-sighted and too limited.

We need to think about the future of this planet –– right now. It is not sustainable to rebuild towns or have such vast forest areas turned to ash every year. Only a handful of enlightened studies have broached this topic. This includes the findings mentioned above headed by the University of Irvine or the “Mortality Cost of Carbon” study, whose scientists stopped to look at the big picture.

“When insurance companies, policymakers, and even the media assess damage from California's wildfires, they focus on the loss of life and direct destruction of physical infrastructure, which, while important, are not the whole picture,” said co-author Steve Davis, UCI professor of Earth system science. “We tried to take a more holistic approach for this project by including a number of other factors such as the ill effects on the health of people living far away and the disruption of supply chains.” –– sciencedaily.com

The study headed by the University of Irvine found that most economic impacts were experienced by industries far from the wildfire in question. Nearly one-third of the total losses of $150 billion calculated were outside of California. They reported that the broader impacts of these climate-driven wildfires were not only more significant than previously estimated but also more widely dispersed, with significant effects felt outside of the state.

The New York Times recently published an article titled, “A Carbon Calculation: How Many Deaths Do Emissions Cause?” The author, Jon Schwartz, poses the question, “What is the cost of our carbon footprint –– not just in dollars, but in lives?”

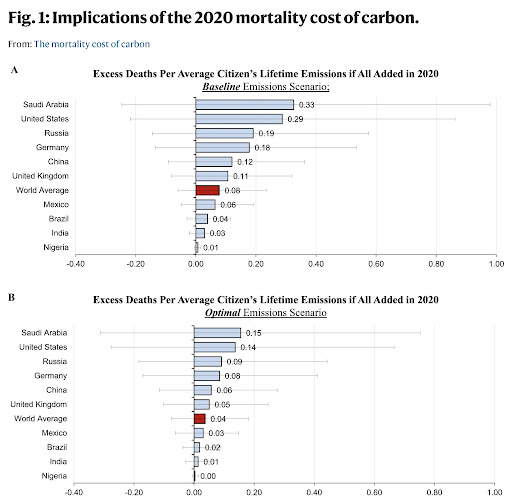

The paper referenced in Mr. Schwartz’s article, “The Mortality Cost of Carbon,” highlights the overlooked certainty that our current level of carbon emissions globally is not sustainable and will claim lives unnecessarily. There is considerable literature that suggests climate change is likely to have an undeniable effect on temperature-related mortality. How many lives are we talking about?

“In total, we find that there are 83 million projected cumulative excess deaths between 2020 and 2100 in the central estimate in the DICE baseline emissions scenario. By the end of the century, the projected 4.6 million excess yearly deaths would put climate change 6th on the 2017 Global Burden of Disease risk factor risk list ahead of outdoor air pollution (3.4 million yearly excess deaths) and just below obesity (4.7 million yearly excess deaths).” –– The Mortality Cost of Carbon

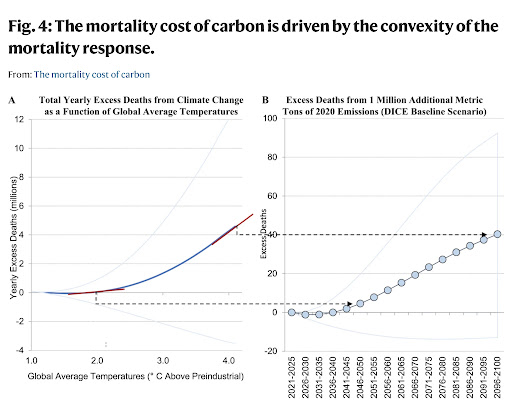

Climate Change is undoubtedly also affecting the duration and longevity of these large-scale wildfires. Suppose the global average temperature exceeds 2 degrees celsius. In that case, the first derivative in the “Mortality Cost of Carbon” is quite steep and only worsens as the average temperature on planet Earth continues to increase. We must realize as a global society that the decisions we make today regarding carbon emissions will have long-lasting repercussions over the next 80 years projected in this study and beyond.

The Social Cost of Carbon, or SCC coined by Mr. Bressler and his findings over years of study, has informed climate policy in the United States, totaling over $1 Trillion in funds allocated to combat this issue. One last sobering calculation offered by Mr. Bressler is his contrast of the carbon footprint affecting mortality rates in different nations.

🆘 Did you know that the carbon emissions generated by fewer than four Americans would kill one person? However, it would take the combined carbon dioxide emissions of 146.2 Nigerians for the same result.

The global carbon dioxide emissions average to cause a single death is 12.8 people. In the United States, it only takes four. What will 83 Million deaths due to carbon emissions over the next 80-years look like? Think about it. What can we do about this sobering assessment now?

That is the question that should be top of mind with business owners and community leaders worldwide. We need to reassess the way we live, our carbon footprints, and legislation regulating the carbon emissions of the most significant industrial carbon emission offenders.

The first line of defense to find ways to protect our air is by testing air quality. Met One Instruments Inc. has been a leader in assisting governments, scientists, engineers, firefighters, and industrial hygienists worldwide by providing the standard of precision air quality monitoring for over 30 years.

Products like the E-BAM Portable Beta Attenuation Mass Monitor are used as the first line of defense for wildland firefighters, acting as a mobile sentry for when winds change, and fires shift. With unique capabilities for dispersion modeling, Met One ambient air quality monitors provide real-time data to alert nearby communities to the threat of wildfires changing course or blanketing an area with hazardous smoke.

More than 15,000 BAM 1020’s are stationed worldwide, providing regulatory air quality measurements in 200 different countries, including across the United States, with the AirNow national air quality monitoring network. Local officials, regulatory agencies, and governmental bodies can be empowered to enact plans and policies to protect the population with this data.

The tools are in place across the US. How can we expand our arsenal of air quality measurement instruments to every corner of the globe? How can we use them to fight the environmental and socio-economic effects of wildfires?

Thank you for joining us in our series about how wildfires affect our environment and the socio-economic impacts we experience in our communities. Would you like more information now? Check out our reading and watch list for this article.

📔 Reading & Watch List…

🎥 Watch this Informative Video “Up & Down: The Wildfire Economy”

🗞 Read NYT Article “A Carbon Calculation: How Many Deaths Do Emissions Cause?”

🗞 Read “What Happens After an Entire Town Burns to the Ground?”

🗞 Read Study by Daniel Bressler “The Mortality Cost of Carbon”

🗞 Read Study from Yale University “Assessing the Environmental, Social & Economic Impacts of Wildfire”